"On February 23, 1923, the Manhattan Beach Fire Department was formally developed."

The Lion Tamers Club, a local leadership group, organized our first volunteer fire department. Following World War I, buses (rapid transit) and automobiles brought an increasing population to our city, which consequently required a more streamlined, functional and professional fire department. On this night, the meeting was held at, you guessed it, the Hardware Store. W.W. Peppers was elected to be the first Fire Chief. It was also during this time period that the fire department was given space at City Hall as a base for its operations, essentially creating our first fire station.

The Lions Tamers Club was a social fraternity, and like other men’s clubs of the time, it served as a social association in addition to serving the community. Its primary mission, however, was to support and advance our local fire department. In May, 1923, our city leased a chemical truck for one year at a cost of $1069.25. They also purchased a siren, two 30 foot ladders, two roof ladders and two chemical tanks. This truck could carry six firefighters and their equipment. As it turned out, however, this vehicle required considerable repair after each and every call. The hills and beach terrain put such a strain on the truck that the brakes had to be constantly relined and the transmission frequently rebuilt. Several streets in the city, namely Manhattan Beach Boulevard and Fifteenth Street, were so steep that the truck had to be turned around and actually backed up the hill.

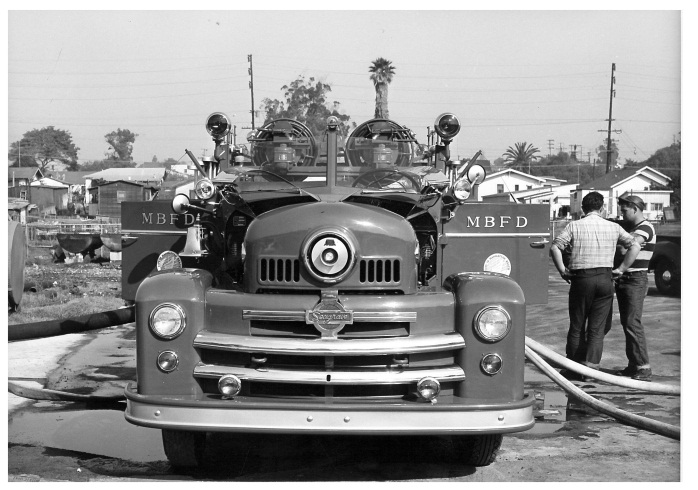

In 1924, Chief Peppers resigned, and Harry Hicks was hired by the city as the first regular firefighter and the first paid fire Chief. He lived in an apartment over the station in City Hall with his wife. He worked 24 hours a day, and was given four days off a month. In October, 1925, the city purchased its first Seagraves Fire Truck, which cost $6,250. It pumped 400 gallons of water a minute, and carried 750 feet of 2 ½ inch hose and 200 feet of 1 inch hose. It also had a 20 foot extension ladder and a 10 foot roof ladder. This was considered state of the art in those days, and our firefighters were thrilled to have such an advanced, sophisticated engine at their disposal. Because of the taller ladders, they were able to also save a number of beach cottages, and at least one two story home that would have otherwise been lost.

In 1924, Chief Peppers resigned, and Harry Hicks was hired by the city as the first regular firefighter and the first paid fire Chief. He lived in an apartment over the station in City Hall with his wife. He worked 24 hours a day, and was given four days off a month. In October, 1925, the city purchased its first Seagraves Fire Truck, which cost $6,250. It pumped 400 gallons of water a minute, and carried 750 feet of 2 ½ inch hose and 200 feet of 1 inch hose. It also had a 20 foot extension ladder and a 10 foot roof ladder. This was considered state of the art in those days, and our firefighters were thrilled to have such an advanced, sophisticated engine at their disposal. Because of the taller ladders, they were able to also save a number of beach cottages, and at least one two story home that would have otherwise been lost.

The demanding work schedule that Chief Hicks was assigned to continued for four years, and during this time, our volunteer firefighters would relieve him so he and his wife could take short vacations. After four years, however, it was decided that a relief man should be hired. In January 1929, Rothwell H. Swain was hired as the first relief firefighter. Swain was to remain attached to our fire department for the next 41 years. In 1947, he was promoted to Chief, which is the position he held for 23 years until his retirement in 1970.

In August of 1930, during the first year of the depression, our fire department decided to reorganize. It appears that some of the citizens preferred a volunteer chief to a paid Chief. Following a vote of the city council, the city agreed and hired a volunteer to replace Chief Hicks. The first of these volunteer chiefs was Newton B. Anthony of the Lion Tamers Club. Many more were to follow in the years following. During this time, firefighters and police exchanged job positions on a regular basis. This was a cost saving measure, but in the 1940’s, it was decided that this practice should cease. It has never returned. It was also during the depression years between 1930 and 1933 that all our city employees took a 10% pay cut. The extra money was used to feed transients, which consisted occasionally of entire family’s. The fire department handed out meal tickets which could be redeemed at a local restaurant, called the Green Shack, on Center Street. The fire department during this time was the place to go for any and all needs, including food. This is a sentiment that continues to this day.

One of the major problems plaguing the city during the 30’s was a lack of an adequate water supply, specifically a lack of properly placed and adequate fire hydrants. We only had 126, and the majority of these were placed west of the sand hills. There were only six hydrants between Sepulveda and Aviation Blvd and south of Manhattan Beach Boulevard. In addition, water pressure was poor due to the use of two inch mains. As the years passed, our water department made it a priority to increase not only the number of hydrants, but also the capacity of the water system through the use of water mains that now exceed 10 inches in many areas of the city.

In 1937, the fire department trained five men who were to work on a rescue squad. These volunteers were provided with basic first aid training and an “inhalator”, and were very successful in their attempt to provide medical care to our citizens. When patients were transported, they were taken to South Bay Hospital. This practice continued until the 1990’s. We now transport to Little Company of Mary and Torrance Memorial Hospital.

In 1939, Manhattan Beach voters ratified a “7-Point Project” bond issue, which primarily designated funds for new streets, services and buildings with the aid of federal funds. Although the federal funds never came, the department acquired a new Mack fire truck ($14,700), which along with increased water capacity and equipment sported an oddball transmission consisting of five forward gears and two reverse. This arrangement helped the engine conquer some of the steeper hills in our city, the same hills that routinely destroyed earlier fire engines.

In 1939, Manhattan Beach voters ratified a “7-Point Project” bond issue, which primarily designated funds for new streets, services and buildings with the aid of federal funds. Although the federal funds never came, the department acquired a new Mack fire truck ($14,700), which along with increased water capacity and equipment sported an oddball transmission consisting of five forward gears and two reverse. This arrangement helped the engine conquer some of the steeper hills in our city, the same hills that routinely destroyed earlier fire engines.

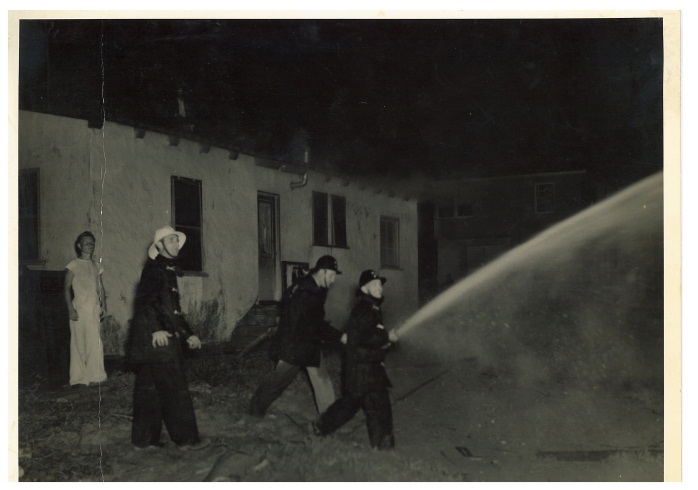

World War II demanded many changes to our department and others. In Manhattan Beach, the city council voted to develop the Auxiliary Fire Department which was manned with 17 volunteers that met once a week for training. They trained in bomb reconnaissance, stood night duty and started sleeping at the station. In 1941, the number of personnel assigned was increased from two to six, and regular firefighters could not leave the city without the express permission of the Chief. In early 1942, the fear of a Japanese attack on the west coast was especially high, and the fire station once again became the center of activity. We now had nearly 60 volunteers, consisting of both auxiliary and paid firefighters. New sirens were installed and training drills were expanded to cover shelling and bombing disasters. Sixteen firefighters left the department during this time to volunteer for military service, as did the current Chief, C.C. Coates, and Rothwell Swain. In 1942, the two-man 24 hour shifts began, and the medical side of the fire service once again elevated itself as a paramount portion of the duties common to fire departments.  We bought our first first-aid vehicle, a Pontiac Sedan, especially equipped for transportation and treatment. In a typical year – 1943 – our department responded to 51 grass fires, 13 house fires, six auto fires and 12 “miscellaneous” calls. Only two calls were false alarms, and many of these calls involved first aid and resuscitation.

We bought our first first-aid vehicle, a Pontiac Sedan, especially equipped for transportation and treatment. In a typical year – 1943 – our department responded to 51 grass fires, 13 house fires, six auto fires and 12 “miscellaneous” calls. Only two calls were false alarms, and many of these calls involved first aid and resuscitation.

Throughout the 1940’s, the fire service gained increased respect from the community for its extremely high skill level, dedication and live saving abilities. Two men were assigned to the rescue squad each shift strictly for ambulance service. They all held advanced first aid cards, and handled only emergencies such as heart attacks and traffic accidents. In 1946, the squad responded to six calls a month. By 1963, that number had increased to 30 per month. Medical aid remains a critical service common to all fire departments throughout the nation.

It was in February, 1951, that a decision was made to building a fire station east of Sepulveda. Heavy rains had washed out large sections of Liberty Village, and although political and financial considerations slowed the progress of this development, Station Number Two was constructed in December, 1954 at a total cost of $36,000. The location was Manhattan Beach Boulevard and Rowell (1400 Manhattan Beach Boulevard). The station still stands at this location, and is currently manned by a single Paramedic Engine company, referred to as Engine 22, with three firefighter/paramedics that protect the east side of our city. This engine also provides the majority of our mutual and automatic aid. In addition, this engine participates in the many strike teams sent to fight the large forest fires we’ve all seen over the years. This station was dedicated to Rothwell Swain, our Chief at the time, in honor of his service and dedication to the department and citizens of Manhattan Beach.

During the 1950’s, we had 21 regular full time firefighters, and 15 volunteers. This period was the end of our heavy dependency upon volunteer firefighters. Ironically, it was in 1951 that our 17 firefighters and 10 volunteers fought a fire that destroyed the Manhattan Hardware. This was, as you remember, the original home of our fire department, and as such carried special significance. It was also in 1951 that our department celebrated a very special honor; the most calls ever run in a single 24 hour shift, eight calls. During this time, the typical firefighter work week was 72 hours: 24 hours on, 24 hours off, with one day off every six shifts.

During the 1950’s, we had 21 regular full time firefighters, and 15 volunteers. This period was the end of our heavy dependency upon volunteer firefighters. Ironically, it was in 1951 that our 17 firefighters and 10 volunteers fought a fire that destroyed the Manhattan Hardware. This was, as you remember, the original home of our fire department, and as such carried special significance. It was also in 1951 that our department celebrated a very special honor; the most calls ever run in a single 24 hour shift, eight calls. During this time, the typical firefighter work week was 72 hours: 24 hours on, 24 hours off, with one day off every six shifts.

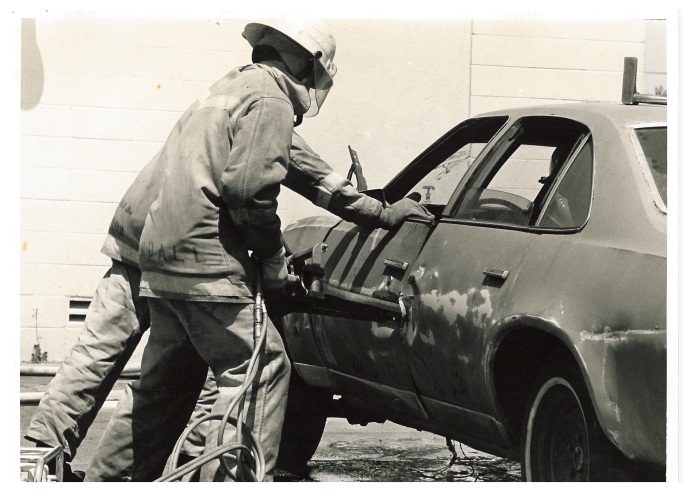

By 1961, we had a total of 38 personnel. These included the Chief, Battalion Chiefs, Captains, engineers, firefighters, volunteers and reserves. Our department had gained statewide recognition as one of the most efficient departments for its size. The science of firefighting was maturing rapidly, and the advances in training and equipment became increasing apparent in our ability to handle larger and more demanding fires and rescues.

By 1961, we had a total of 38 personnel. These included the Chief, Battalion Chiefs, Captains, engineers, firefighters, volunteers and reserves. Our department had gained statewide recognition as one of the most efficient departments for its size. The science of firefighting was maturing rapidly, and the advances in training and equipment became increasing apparent in our ability to handle larger and more demanding fires and rescues.

It was during the 1960’s that an organization formed by our city firefighters, the Manhattan Beach Firemen’s League, fought for and achieved a more equitable work schedule. Although the League’s original request to reduce the hours worked per week to 63 failed initially, it was finally authorized in August, 1969. This work week has since been reduced to 56 hours per week, and our firefighters currently work a 48 hour shift on, with 96 hours off. This schedule repeats itself throughout the year through the use of three shifts. A, B and C shift take turns manning our stations so that service is available each day of the year.

In 1970, Chief Rothwell Swain retired after 41 years of service. In March of the same year, Lewis Wright was appointed the position of fire Chief. He had joined our department in 1952, and had worked his way through the ranks. This was a continuation of our department’s policy of promoting individuals from within our own ranks. It was shortly after his appointment that the California Legislature passed the Mobile Intensive Care Unit Paramedic Act. This act provided that certain individuals, trained to very high standards, would be certified to provide specific medical emergency techniques in the field, and they would be certified “Paramedics”. A special team of five firefighters began training at South Bay Hospital to participate in the most advanced primary responder medical training available. They completed their training July 14, 1973, and were immediately put into service, saving the life of a teen age boy that same afternoon. It soon became evident, however, that the vehicle assigned to the Paramedics was inadequate, and through a fund drive launched in Spring, 1973, $13,000 was raised for the purchase of a new van. Everyone participated in the fund drive, including the Kiwanis, who sponsored a July circus. Our city councilmen even pumped gas, and there was a buffet dinner at one of the local restaurants. Everyone got involved, and many more events followed. The end result was a new paramedic van, painted a distinctive yellow, equipped with all the advanced medical equipment needed for this new realm of patient care.

Tremendous media excitement accompanied the beginning of this new era of in-field medical treatment. “Emergency”, a drama series that ran from January 22, 1972 until September 3, 1977, featured our two favorite paramedics, Johnny Gage and Roy DeSoto on Squad 51 of the Los Angeles County Fire Department. They saved everyone they touched, and always transported to the famous Rampart Hospital. This show launched the paramedic program into the national limelight, and it has remained a fixture of fire department services to this day. We have advanced our skill levels and equipment considerably since then. Our modern paramedics are now capable of delivering emergency room level patient care in the field. On our department, everyone is, or has been, a certified paramedic. Every Manhattan Beach fire apparatus you see is manned with certified and extremely well trained paramedics.

Since the 1970’s, the fire service has continued to evolve into the very effective service you see daily on the streets of Manhattan Beach. We have had several chiefs since those days, including Tom Wilson, Keith Hackamack, and Dennis Groat.